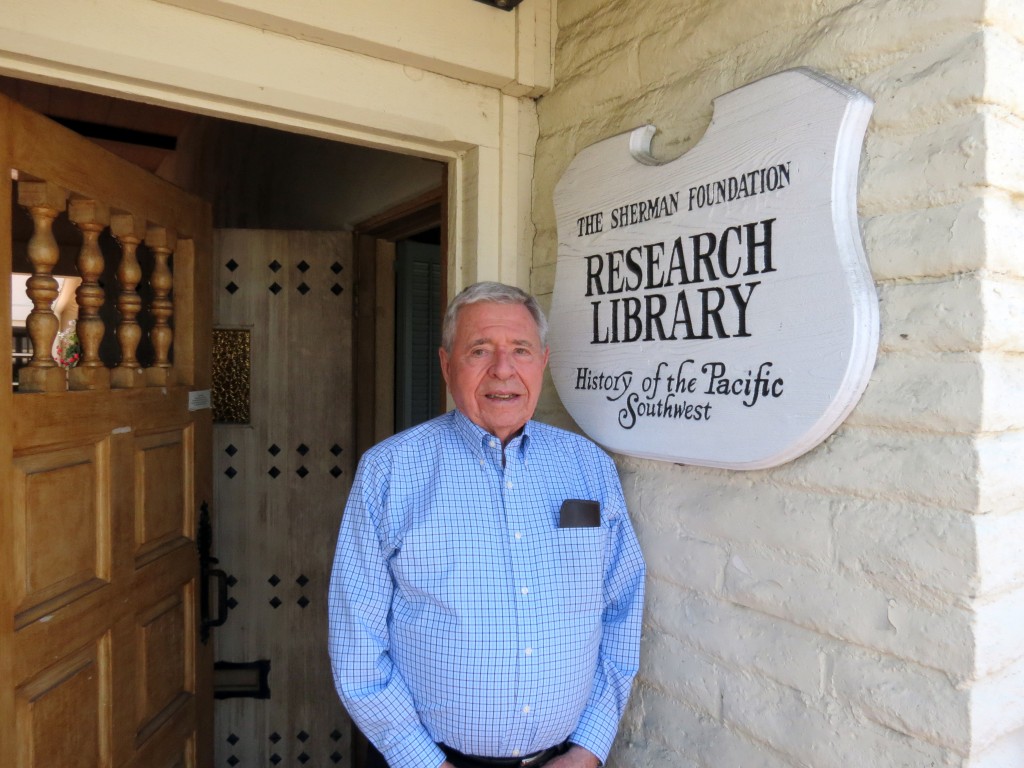

After nearly half a century, Dr. William “Bill” Hendricks is retiring from his position as director of Sherman Library.

Hendricks, who turns 86 next month, began working for the Sherman Foundation on July 1, 1965.

“Just two years short of half a century,” Hendricks said with a laugh.

A lot has changed during those 48 years.

He started as a researcher and developed the library a few years later. He wore a suit and tie for many years. He saw several bookstores go out of business. He’s worked his way through a number of offices. He helped build the library up and expand the collection. He went part-time when he was 65-years-old, working just two days a week, Wednesday and Thursday. He’s read countless books.

After so many years, it’s time to retire, he said, but he has mixed feelings about it.

“In some ways retirement is appealing,” Hendricks said. “And in some ways, since I started the library, I have a close attachment to it.”

It all started when he was working on his doctorial dissertation on 20th century development of the Mexicali Valley, 840,000 acres of which were owned by the Colorado River Land Company. This led him to Arnold Haskell, president of CRLC and the right hand man for Moses Hazeltine “M.H.” Sherman (who had been a partial owner of the CRLC).

Hendricks met Haskell in his Corona del Mar offices, where Haskell asked him for a biographical sketch of himself, an outline of his proposal and a list of the 15 most prominent people he knew. After Hendricks provided all of this, Haskell asked him for letters of recommendation from those 15 people, people that a young Hendricks knew but hadn’t yet gotten permission from to use their name, so he worried a bit about referencing them.

“Every single one of them came through (Haskell) informed me,” Hendricks recalled. “And a couple of them I had been very doubtful about.”

Then, to Hendrick’s astonishment, Haskell offered him a job.

“I thought it over and decided to give it a whirl,” he said.

He had been teaching at local universities, including Chouinard Art Institute (now California Institute of the Arts), California State University, Los Angeles, and University of Southern California.

“I thought I’d be doing that the rest of my life,” he said.

“When I first started I wore many different hats,” Hendricks said.

His title was director of research, but he was also a collector, organizer, record keeper, newsletter editor, historian, and more.

“As you get older and all these hats you used to wear, you just can’t do all those things,” he continued.

The first order of business was to finish his dissertation.

He was having to go to Los Angeles often to read books, documents and reference materials. Haskell soon suggested that he start collecting the books they needed. Not long after that, the two had a meeting and Hendricks noted that they had some unique books and materials that weren’t available anywhere else nearby, so they should open it up to the public. By the early 1970s the library had gotten it’s start.

“So that was the birth, sort of accidentally, of the library,” Hendricks said.

He also started organizing the Sherman papers, truck loads of them.

“At first, a lot of it was… organizing,” Hendricks said. Sherman had held on to a lot of his papers thinking they may one day be useful in explaining how the development occurred in the area. But they had been transferred to various offices throughout the years, so Hendricks had to start organizing and storing all of it properly. At one time, there were eight people going through all of them and storing them in the empty storefronts and houses on the block that the foundation was buying up.

On his trips to LA he would hit up both small and big book stores, looking for books to add to the library’s collection. He also interviewed many people regarding historical information and documents, including Lillian Roberts, aka Mrs. Harry H. Culver the founder of Culver City. He often dealt with book dealers, some of them a bit odd, he said, like the man who would ask for a high amount for an item, maybe around $100, and then after Hendricks rejected the offer, came back significantly lower, for just $30.

“He was just pulling numbers out of thin air,” he said with a laugh.

There are a lot of stories like that.

“Oh gosh, there have been all kinds of things that have happened over that span of time,” he said.

One of those amusing stories is from many years ago when he was in Los Angeles having lunch at the Hotel Bel-Air with a man who often donated to the library. He frequented the restaurant there and as they waited for a table the waiter brought the man’s favorite hors d’oeuvre: Rice Chex.

“It was cereal,” Hendricks recalled with a laugh.

The man explained that he doesn’t eat wheat, and the cereal was a great snack. He continued the conversation as they sat down at a table in the main room, describing his background in cattle and dairy business, which segwayed into how a cow’s stomach worked.

The man, who was slightly deaf and spoke in a loud voice, asked, “Do you know anything about a cow’s stomach?”

“Everybody’s head in the room went up,” Hendricks said. The waiter hid behind a post and started laughing to himself. “By the time he finished telling me that, we had the room to ourselves.”

“That’s always been a memorable story,” he added.

If he were to go back in time, with all of his knowledge and experience now, he would still accept that fateful offer made by Haskell.

It was a gamble, he said, to take the job not knowing where it would lead, or if it would go anywhere at all.

“I could have been out of here in two or three years,” he said. “I had to make some judgments. I thought it was genuine and that (assessment) turned out to be (correct).”

Hendricks is particularly proud of some one-of-a-kind papers on land deals, business transactions, old maps and other documents.

“Books get written from papers,” he said, so they are an important part of documenting history.

The oldest book in the library’s collection is from 1703 from London, telling the story of some English seaman sailing off the coast of California.

He’s pretty proud of their collection, nearly 20,000 books and documents, as well.

“The fact that we’ve managed to accumulate what we have on a very slim budget,” he said. “That’s gratifying.”

They were able to do a lot with a little, he explained.

After retirement Hendricks, a Laguna Hills resident, plans on spending some more time at his place in Palm Springs. He also has several research projects in mind he might work on, including something regarding Arnold Haskell, who died in 1977.

Overall, he had some great experiences and success at the library, but there are also things he wished had happened over the years, changes he would have made if he could have.

“It’s been a very interesting experience,” he said. “Not everything has gone the way I hoped… (But) it’s been a pleasant experience… A lot of fun.”

For more information, visit slgardens.org/library