After nearly two decades practicing perfectionist dentistry, longtime Newport Beach resident Richard Mather, DDS, took to heart that classic country western song, “Take This Job and Shove it;” so he did. That was 1989.

After nearly two decades practicing perfectionist dentistry, longtime Newport Beach resident Richard Mather, DDS, took to heart that classic country western song, “Take This Job and Shove it;” so he did. That was 1989.

Mather realized that his world had to expand way beyond looking all day into a bacteria-infused orifice that on average measured only two-inches in diameter.

He recognized that every time he, his wife, Pam, and their two children, Rich and Jill, happily drove 12 hours north to their Northern California cabin at Fall River Mills, he drove morosely home so that he could drill and fill on people who just didn’t’ want to be there.

What Mather loved doing and never tired of was woodworking. His wide receiver-sized hands just felt better clamped about a carpenter’s drill rather than the eight-hour-a-day pencil grip around a miniscule dental drill.

Truth be known, he also tired of the five percent of patients who seemingly lived to complain, even though he restored smiles on those people who probably seldom smiled anyway.

Truth be known, he also tired of the five percent of patients who seemingly lived to complain, even though he restored smiles on those people who probably seldom smiled anyway.

Since childhood, Mather built and rebuilt things, including the interior of their family cabin. This, then, was his “future.” He and Pam bought several old homes in Corona del Mar, gutted them, then brought them to interior perfection for assured resale.

“The first two were learning experiences, we made money on the second,” Mather recalled.

Then the recession hit.

On to the next creative venture: computer graphics for architectural renderings, a skill that he had honed while planning their CdM renovations. This creative undertaking took off faster than a high-rise residence built in Beijing, and lasted longer – from 1992 to 2013.

In fact, Mather’s renderings were so photographic and detailed that an angry, screaming plans inspector for a neighboring city accused Mather’s clients of constructing the building without permits, then presenting photographs of the finished building.

The building still exists; the inspector is gone.

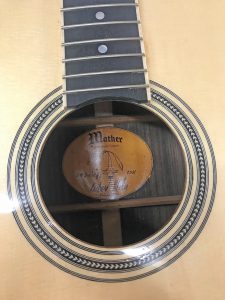

Creative and challenging as that was, Mather needed new undertakings, so he retired from computer graphics and “retired” to his garage woodshop, where daily he blends the skills of the woodworker with the honed motor skills of the dentist and the creativity of an artist to build one-off guitars.

So finely built are they that Mather, now officially a luthier (guitar maker), may at least become known as the guitar Stradivarius of Newport Beach.

Of all Mather’s creative undertakings, guitar making is the most demanding, and satisfying, he said.

There are moments of truth in certain undertakings. In diamond cutting, it’s when a craftsman splits the raw stone before the faceting process can begin. In luthier craftsmanship, it’s virtually every step of the process, for an imperfect strike of a hammer on chisel will ruin months of meticulous work, thereby damaging any chance of the promise of perfect resonance.

Already an accomplished woodworker with enough garage-based tools to make Home Depot jealous, Mather discovered that he needed an entire collection of very specialized tools, such as luthier files that spanned sizes that Mather called “tiny and tiny to medium sized files of varied shapes, multiple jigs, low-angled jack planes, block planes button planes, various shapers, a thickness sander, and router table that allowed for more shaping.”

Prior to purchasing the thickness sander, Mather said he had to scrape the back and sound boards, top and sides by hand planning to an even thickness of down to 2.2 mm. The multiple types of wood each required its own treatment, he said, and included such types as rose wood for the sides and back, Englemann spruce for the top sound board, ebony for the finger boards, and mahogany and maple for the neck.

In all, there are nearly 100 parts to one of his six-stringed Orchestra Model guitars, and the only manufactured parts he will include are the finger tuners and strings.

Mather plans on making but 10 guitars. The first, he said, goes to Pam. Number two may go to his son, who, Mather said is a very accomplished guitarist.

The rest of the order is to be determined. Nobody should be in too great a hurry, however. Mather has been working on Number One since last March.

The electric thickness sander should accelerate the crafting, he said. Accuracy of sanding and milling is crucial; as is joining the parts so that each piece blends seamlessly with the other when glued in place.

And this is only part of the art. Unbeknown to most, guitar making is also mathematics and engineering. For example, fret slots (according to the plans) must be measured to 10,000th of an inch in proper spacing from their sister frets. It is so precise, “One can only really achieve near perfection,” Mather opined, “or be as perfect as one can be.”

There’s one more step: achieving the gloss.

“Getting a perfect lacquer job can be frustrating, and time consuming,” Mather sighed. But when done correctly, as on Guitar Number One, the finish makes an ice cube feel like the surface of a rocky road.

So that wife Pam isn’t what Mather calls “a guitar widow,” he always welcomes her company during the process. And Pam says that she doesn’t regret one second that he spends so much time in the garage. She loves being there with him.

There is a relationship between being a dentist and a luthier. In both, Mather always sought and seeks perfection.