The Orange County Museum of Art recently opened “Jack Goldsteinx10,000,” an overdue retrospective of an innovative artist appreciated among aficionados of conceptual art and re-discovered by young artists in the United States and Europe. Even if the sequencing is unintentional, the Goldstein show makes a good sequel to “State of Mind: California Art Circa 1970,” the OCMA exhibition which garnered acclaim as a component of the Pacific Standard Time series of exhibitions initiated by the Getty Research Institute (Pacific Standard Time: Art in L.A. 1945-1980).

The last Goldstein retrospective had been staged in Geneva, Switzerland, in 2003, and this one is the first in the US.

Curated by Philipp Kaiser, senior curator at The Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) and soon to be director of the Museum Ludwig in Cologne, Germany, the show is arranged chronologically, beginning with a nine-feet long 1971 wood sculpture that represents his beginnings in a medium that ultimately did not pan out for him.

But, reported disappointment at his peers tepid response to that work led to more interesting fare, a manic hopscotch from medium to medium including performance art, photography, assemblage, painting, musical “composition”, word art and combinations of the above plus an ever increasing array of tangents on anything that moved him.

Describing Jack Goldstein as man of contradictions is an understatement. On one hand, he was a “salon painter” who wanted to sell, but then also avoided revealing himself as the “author” of said paintings, hiring others to execute them according to his instructions (think of a precursor to Jeff Koons) in spray paint to avoid identifying brushstrokes.

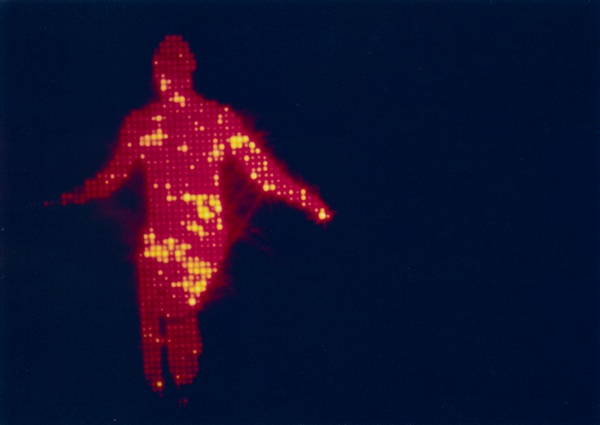

As a performance artist, he took the spotlight but then produced endless video loops of a dog barking (Shane) or conjured images of tornadoes or electrical storms. For him, it was not just about art but control over any medium and subject he chose.

To that end, he rented sound equipment to record music/sounds and cut his own vinyl records but designed their covers in the minimalist vein of John Baldessari, a mentor/role model. Enthralled with the production aspects of Hollywood, he used the same equipment as filmmakers, yet deployed it to create images vastly different from the “dream factory’s” output of the time. Then again, a video image of a gleaming knife, brings to mind Roman Polanski’s 1962 (non-Hollywood) cult film “Knife in the Water.”

Goldstein came into his own after graduating from CalArts, a school ideologically shaped by instructors like Baldessari and students like David Salle. Along with now illustrious peers like Barbara Krueger, he became keenly aware of the power of pictures in contemporary media. Savvily, he re-purposed icons such as the iconic MGM lion by clipping it out and placing it against a blood-red background. While the beast roars in an endless loop it evokes eager anticipation of more to come until realization sets in that nothing else is going to happen.

One might think of the beast as a metaphor for Goldstein’s life. Born in Montreal in 1945, he moved to California, migrated to New York were he was celebrated by gallerists and collectors, found appreciative audiences in Europe but, after returning to California, sank into obscurity and drug addiction and ultimately committed suicide.

“A Ballet Shoe,” is a 1975 video and a pictorial allusion to the power of the unseen and the imagination processes it triggers. The hand that unties the the ribbons of the dancer’s toe shoe also stops her performance, or perhaps she no longer wants to move. It’s up to contemporary viewers, bombarded with countless images un-foreseeable to Goldstein and his contemporaries, to re-discover the artist and perhaps propel him toward the recognition, even fame perhaps, that eluded him during his lifetime.

Kaiser says that, especially in Europe, Goldstein’s life and death have achieved mythical proportions among young artists who see him bridging gaps between conceptualism, minimalism and pop-art, as a connector between the ‘60s and the ‘80s, and as a tragic figure who struggled for recognition during his life and ended it in a macabre performance by hanging himself.

“He was a man ahead of his time, a true radical,” said Kaiser.

“Jack Goldsteinx10,000” through Sept. 9

Orange County Museum of Art, 850 San Clemente Drive, Newport Beach.

Information: 949-759-1122; ocma.net

By Daniella Walsh