Authorities revealed a wide-reaching college admissions cheating scheme this week that included millions paid in bribes, as well as falsified exam scores, achievements, and athletic accomplishments, and a Newport Beach college prep business is at the center of it all.

Authorities charged 50 people Tuesday in connection with the largest college admissions scandal in Justice Department history.

The scandal involves university athletic coaches, college exam administrators, and wealthy parents across the country, including Hollywood celebrities, CEOs, business executives, a fashion designer, and more.

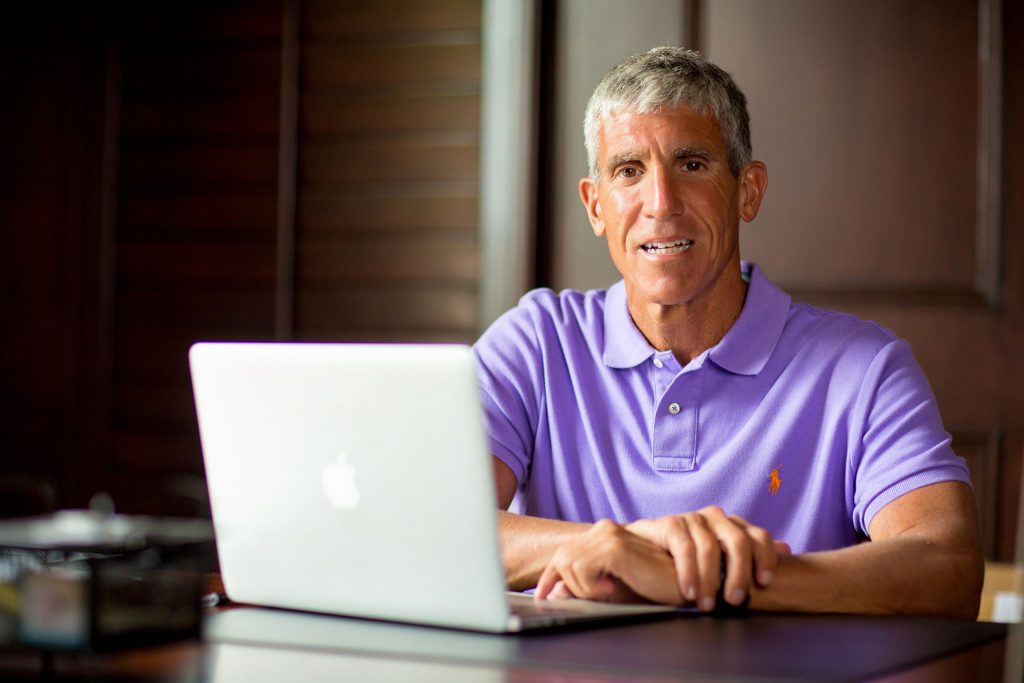

At the top of the list of those charged is William “Rick” Singer, 58, who founded Edge College & Career, LLC, also known as “The Key,” based in Newport Beach. He also served as the CEO of the Key Worldwide Foundation, a nonprofit corporation that he established as a purported charity.

Photo: Facebook

Singer was charged with racketeering conspiracy, money laundering conspiracy, conspiracy to defraud, and obstruction of justice.

He pled guilty to all counts on Wednesday. Sentencing is scheduled for June 19 at 2 p.m. He was released on a $500,000 unsecured bond.

A few parents involved are also local, according to authorities: Michelle Janavs, 48, of Newport Coast, a former executive of a large food manufacturer; and I-Hin “Joey” Chen, 64, of Newport Beach, operates a provider of warehousing and related services for the shipping industry. Former CEO of Newport Beach-based investment management company PIMCO, Douglas Hodge, 61, of Laguna Beach, was also listed.

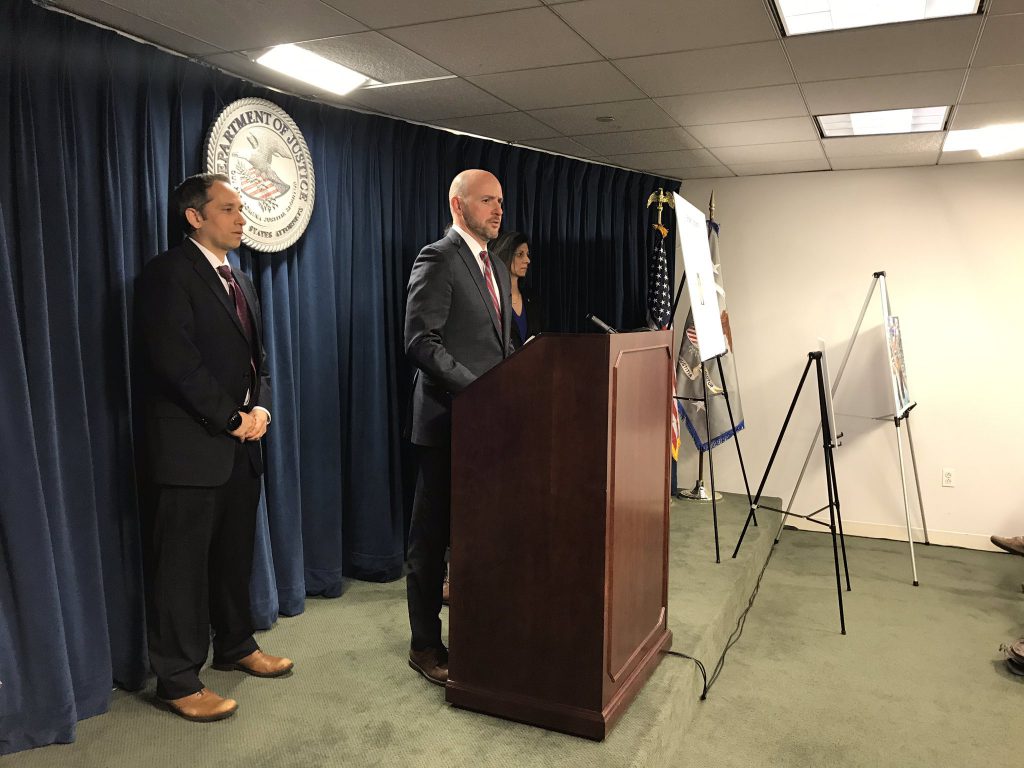

Parents spent anywhere from $200,000 to $6.5 million to guarantee admissions to elite schools for their children, according to United States Attorney for the District of Massachusetts Andrew Lelling.

“There will not be a separate admissions system for the wealthy,” Lelling said. “And there will not be a separate criminal justice system either.”

The scheme centered around cheating on college entrance exams and the admission of students to elite universities as purported athletic recruits

Since the scheme began in 2011, parents allegedly paid Singer approximately $25 million to bribe coaches and university administrators to designate the clients’ children as recruited athletes, to ensure their admission into the elite universities.

Prosecutors claim the scheme used the façade of Singer’s charitable organization to conceal the nature and source of the bribes.

According to the indictment, Singer would bribe SAT and ACT officials to allow a third party to secretly take the exams in place of the actual students or replace the students’ exams with his own. Singer also often allegedly advised parents to ask for extended time on the tests by claiming their kids have learning disabilities.

“In many instances, the students taking the exams were unaware that their parents had arranged for the cheating,” according to authorities.

The couple of test administrators Singer worked with accepted bribes of as much as $10,000 per test. Singer’s clients paid him between $15,000 and $75,000 per test, with the payments structured as purported donations to the KWF charity.

Another “side door” arrangement included bribing university athletic coaches and administrators to facilitate the admission of students to elite universities under the guise of being recruited as athletes, regardless of their athletic experience and abilities.

Athletic coaches from University of Southern California, Yale, Stanford, Wake Forest and Georgetown universities, among others, are implicated.

In one instance, Singer was paid $1.2 million to get a student into Yale, which he did by falsely claiming the young woman was captain of prominent women’s soccer team in southern California. After she was admitted into Yale, Singer sent the women’s soccer coach $400,000 from the KWF charitable accounts.

— US Attorney MA Twitter

Prosecutors describe similar stories involving water polo, sailing, crew, track and field, volleyball, and other sports.

Newport parent, Janavs, allegedly participated in both the college entrance exam scheme and the athletic recruitment scheme to facilitate her daughter’s admission to USC as a purported beach volleyball recruit in 2017.

Janavs’ daughter received additional time to take the ACT, which Singer arranged to be taken at a controlled location. An administer from Florida was flown in to oversee the exam. Her daughter received a 32 out of 36 possible points.

Janavs paid Singer, through KWF, $50,000, which, in part, allegedly paid off the test administrators.

In fall 2018, the falsified ACT test scores were included in Janavs’ daughter’s application to USC, according to authorities. Her application also purposed she was a beach volleyball recruit, and although she “played volleyball in high school, she did not play competitive beach volleyball,” the criminal complaint explains. Her profile sent to the school included photos of her playing the sport and “falsely described her as the winner of multiple beach volleyball tournaments in California.”

In several emails and calls between Janavs and Singer between 2017 and early 2019, transcribed (in part) in the criminal complaint, they discussed the ACT exam scheme, how to present Janavs’ daughter as a volleyball player, and where to send the payments.

In November, Janavs called Singer about repeating the ACT scheme for her younger daughter. Pointing out that her daughter might become suspicious if they change locations and dates for the test, she asked how to explain the changes. Singer instructed her to say she didn’t want her to miss any school and that it’s more convenient this way.

“She’s smart, she’s going to figure this out,” Janavs said. “Yeah, she’s going to say to me– she already thinks I’m up to, like, no good.”

Her older daughter “didn’t care” and thought the test was “bullshit,” she noted, but her younger daughter was studying hard and wanted to score high.

Adding that the school officials might also question why both of Janavs’ daughters requested an alternate time and location for the test and then ultimately score high, Janavs dismissed any concern.

“Yeah, they’re not stupid either, but whatever, I don’t care,” Janavs said. “They can’t say anything to me. I mean they’re going to be suspicious that every kid I have does so well somewhere else, but that’s okay.”

In more phone calls in January and February, Janavs and Singer discussed payments, test scores, and how to secure her daughter’s score. In two separate payments in February, Janavs wired a total of $50,000 to KWF.

Another Newport parent, Chen, paid $75,000 to The Key in exchange for a controlled ACT test administrator and for his son’s answers to be corrected.

At the direction of law enforcement, Singer called several of the parents, including Chen, saying the charitable foundation was being audited by the IRS. He instructed Chen and the other parents to claim the payments were to “help underserved kids,” to which Chen and others agreed.

The charge of racketeering conspiracy provides for a sentence of no greater than 20 years in prison, three years of supervised release, a fine of $250,000 or twice the gross gain or loss, whichever is greater and restitution. The charge of conspiracy to commit money laundering provides for a sentence of up to 20 years in prison, up to three years of supervised release, and a fine of not more than $500,000 or twice the value of the property involved in the money laundering. The charge of conspiracy to defraud the United States provides for a sentence of no greater than five years in prison, up to three years of supervised release and a fine of $250,000. The charge of obstruction of justice provides for a sentence of no greater than 10 years in prison, three years of supervised release and a fine of $250,000.

Most of the parents involved are charged with conspiracy to commit mail fraud and honest services mail fraud, and of conspiracy to commit wire fraud and honest services wire fraud, which provide for a sentence of no greater than 20 years in prison, three years of supervised release, and a fine of 250,000 or twice the gross gain or loss, whichever is greater.